The Lion King

Slightly sprawling and rain-battered, but nevertheless looking spectacular in the garden at the moment is one of my favourite plants, and a worthy first plant profile for my blog: Leonotis leonurus, or Lion’s Ear (the name literally means “lion-coloured lion’s ear”).

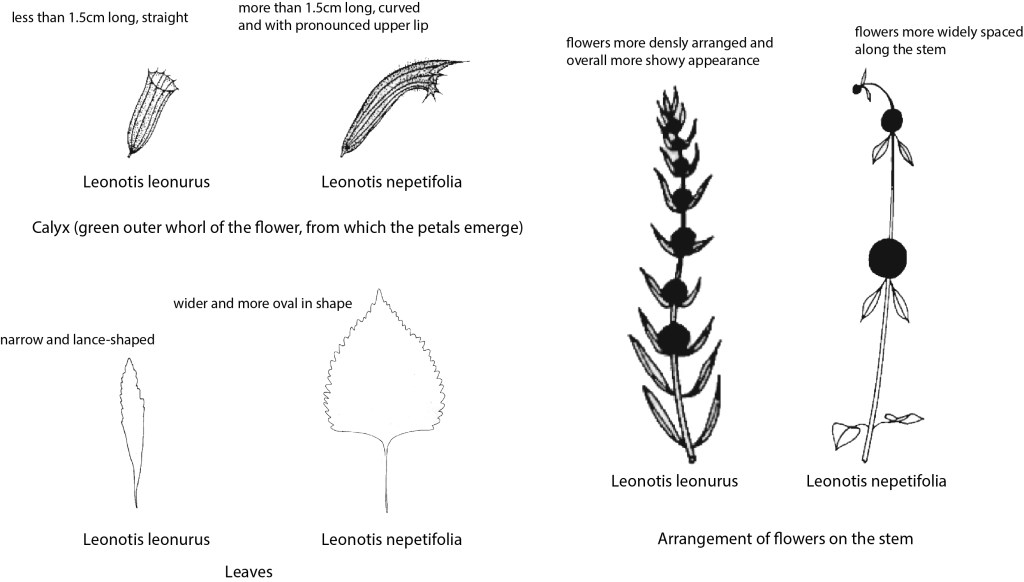

Leonotis leonurus is one of nine species of Leonotis, all of which occur in the wild in tropical and southern Africa. Only two are widely grown in horticulture, the other being L. nepetifolia, which has wider, more oval-shaped leaves than the narrow lance-shaped leaves of Leonotis leonurus, and is an annual, reaching flowering size from seed in a single season, and would therefore be a good substitute in colder areas, where the perennial Leonotis leonurus would not survive over winter. Leonotis nepetifolia seeds are sometimes sold labelled as Leonotis leonurus, but it is easy to tell the two species apart:

Leonotis leonurus is a member of the Lamiaceae family, which is in the order Lamiales. The Lamiaceae family is the sixth largest of all flowering plant families, with over 7,000 species, and so has been divided up into several sub-families to help botanists get a handle on it. Leonotis is grouped in the subfamily Lamioidae, along with relatives including Phlomis, Lamium, Stachys and Molucella. All have a two-lipped corolla (the part of the flower made up of petals) with four stamens (the male flower parts, containing pollen) arranged under the upper lip.

Leonotis leonurus has a long and fascinating history, and was one of the earliest South African plants to be cultivated in Europe. It is thought that the Lamioidae tribe originated about 24 million years ago, with the common ancestor of Leonotis and its other living relatives evolving around 10 million years ago, probably in Asia, before diversifying and spreading to Africa, where Leonotis subsequently evolved. In fact, recent research based on DNA analysis has revealed that Leonotis, though morphologically distinct, is not genetically distinct from its closest relatives, members of the genus Leucas.

Leonotis is distinguished morphologically by the dense orange-red hairs covering the corolla, and the short lower corolla lip that withers within an hour or two of the flower opening, while the rest of the flower lasts for several days. The flowers of Leonotis are pollinated by sunbirds, rather than insects, and it is thought that these morphological characters may be an adaptation to bird pollination: the large lower lip of most Lamiaceae flowers provide a landing platform for pollinating insects and are often showy. Having an insignificant lower lip discourages insect visitors, and the orange colour could be particularly attractive to birds. Leonotis, rather than being a genetically distinct group, may in fact simply be bird-pollinated Leucas, and the name may change in the future to reflect this.

Leonotis leonurus remained in Africa until European explorers arrived in the 17th century, searching for new additions to their gardens. One such explorer was the Dutch botanist and physician Paul Hermann, who in 1672 was sent to the Dutch East India Company in Sri Lanka to be the medical officer. He called at the Cape of South Africa on the way, where he made the first known pressed specimens of local plants. In 1680 he returned to the Netherlands to become professor of Botany at Leiden, where he died before he had a chance to write up an account of the 791 plants he had collected at the Cape. However, while at the Cape in 1672, he had given some specimens and seeds to the ship’s surgeon, who after returning home gave the specimens to the Danish scientist Thomas Bartholinus who used them as the basis for an article he published in 1675, which is thought to be the first ever published list of South African Plants, and where the earliest known illustration of Leonotis leonurus can be found.

Plants were soon growing in Dutch gardens and the seeds were gradually distributed through the network of keen botanists and gardeners that existed across Europe at the time. In 1712 it was first grown in the UK by the keen gardener and botanist Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort, who was responsible for many introductions to UK horticulture, at her London garden at Chelsea, and she no doubt provided material for her neighbour the Chelsea Physic Garden, which was soon to enjoy its golden age under the celebrated head gardener Phillip Miller.

These Plants are very great Ornaments in a Green-house, producing large Tufts of beautiful scarlet Flowers in the Months of October and November, when few other Plants are in Perfection, for which Reason a good Green- house should never be wanting of these Plants, especially since they require no artificial Heat, but only to be preserved from hard Frosts, so that they may be placed amongst Oranges , Myrtles, Oleanders etc.. in such a Manner, as not to be too much over-shaded with other Plants; but that they may enjoy as much free Air as possible in mild Weather… These Plants will grow to be eight or nine Feet high, and abide many Years; but are very subject to grow irregular, therefore their Branches should be pruned early in the Spring, in order to reduce them to a tolerable Figure; but they will not bear to be often pruned or sheer’d, nor can they ever be form’d into Balls or Pyramids, for if they are often shorten’d, it will prevent their flowering.

180 years later Miller’s advice seems apt, since my own plant has survived the last two winters planted out without protection (in the company of oranges and oleanders), situated against the south-facing wall, where I cut it down to about 30cm from the ground in early Spring each year, in an attempt to keep its rapid, sprawling growth under control (though I took my eye of the ball this year and it quickly outgrew its allocated space). It’s over 300 years since this species was first grown in the UK, and it surely deserves to be more widely grown. Why not try growing it in a sunny, sheltered spot or, for the more risk- averse, in a container which can be brought into a cool, sunny porch or conservatory during hard frosts?

Leonotis leonurus

Countries where L. leonurus grows in the wild

Another new name to learn perhaps.